With wildfire season already in effect across B.C., our expert shares recommendations on how to stay informed and healthy when conditions are smoky.

The 2023 wildfire season was the most destructive on record in British Columbia, resulting in over 2.8 million hectares of land and forest burned and tens of thousands of evacuations. In preparation for an early wildfire season this year, Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute researcher and Vancouver General Hospital (VGH) respirologist Dr. Emily Brigham shares crucial advice on how best to prepare for the smoky season ahead.

Q: How do we know when wildfire smoke levels are unhealthy?

A: If you can see or smell smoke, the risk is high. But you can’t rely on your eyes and nose alone. Even if you cannot see or smell smoke, there can still be poor air quality from wildfires. That’s why public health agencies and doctors recommend checking air quality reports frequently — more than daily if possible, as conditions can change quickly — during wildfire season.

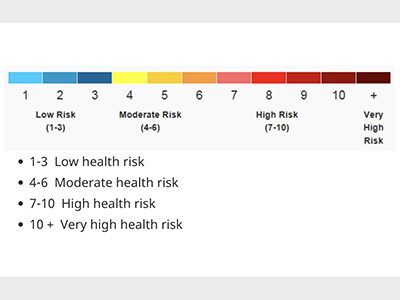

Canada and B.C. monitor the concentrations of three air pollutants with known health effects: ground-level ozone, nitrogen dioxide and fine particulate matter, also known as PM2.5. The concentrations and known health effects of each of these pollutants are used to calculate something called the Air Quality Health Index (AQHI). In B.C., experts have taken this one step further, using a modified version of the AQHI during wildfire season to better account for the health effects of smoke.

You can access your local AQHI on the WeatherCan app, among other places. In some parts of B.C. that are far away from a government monitoring site, local networks have been set up that specifically monitor PM2.5, which is the pollutant of highest concern for health effects from wildfire smoke. You can also sign up for alerts through the Government of B.C. and the Hello Weather phone line through the Government of Canada. Consider helping friends and family members who may have difficulty accessing this information.

Q: What makes wildfire smoke and its health effects different from other types of air pollution?

A: Wildfire smoke is a complex mixture of pollutants, which can vary based on what items are being burned in the fire, such as forests, buildings and other infrastructure. There presently is insufficient evidence for unique effects of wildfire smoke compared to other forms of air pollution. However, several studies suggest that inhaling PM2.5 wildfire smoke may have higher toxicity and come with a higher risk of respiratory hospitalizations compared to PM2.5 from other sources.

Q: Who is at higher risk of experiencing health effects from wildfire smoke?

A: Individuals at higher risk include those with underlying health conditions — including lung or heart disease — as well as pregnant women, infants, children and older adults.

Q: What short-term health concerns are associated with wildfire exposure?

A: In the short-term, symptoms can include irritation of the eyes, nose and throat, as well as headaches and mild wheezing and coughing. If you experience any of these symptoms, move to an area with cleaner air. More severe, acute effects include shortness of breath, severe coughing, heart palpitations, dizziness and/or chest pain, which require medical attention.

Wildfire smoke exposure can increase the risk of respiratory infections in adults and children, along with ear infections in children. Individuals with these infections should take extra care to avoid smoke.

Q: Are there also long-term health risks of wildfire smoke?

A: Because wildfire smoke is episodic, and exposure can vary widely in some places from year to year, it is taking some time to figure out the long-term effects of wildfire smoke exposure. Studies of wildland firefighters who are exposed to high levels of smoke season after season suggest that chronic exposure to wildfire smoke might impact lung function and the risk of developing asthma. However, we do not yet know how this compares to the effects we might see in the general population. Emerging studies have linked wildfire smoke exposures to cancer risk and birth outcomes, such as premature birth, but this research is still early and needs to be verified. Regardless, protective measures are important when possible.

Q: What precautions should I take to protect my lungs both indoors and outdoors when conditions are smoky?

A: Public health recommendations focus on optimizing cleaner indoor air, as this is where most people spend their time. During smoky days, you ideally want to restrict the amount of smoky air that enters your home or office and clean the indoor air using an air purifier machine with a high efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filter, which is the preferred technology for removing PM2.5. You can also make your own air purifier with a box fan and a filter. Avoid air purifiers that use electrostatic technology as they can produce other air pollutants. Also, try to minimize the production of indoor air pollution by limiting cooking practices that release air pollution like frying and roasting, and avoiding burning candles or using hairspray and other aerosols. Keep windows closed if this does not prove problematic for cooling indoor air; or, move to a space where the air is both cleaner and cooler, such as a public recreation centre, library or mall.

Some regions set up air shelters during wildfire smoke events, which may be listed on your local government website or by contacting the municipal council offices in your community. If you need to go outside, wear a respirator, such as a KN95 or N95 mask, for the best protection. A triple-layer medical mask provides moderate protection.

The BC CDC Wildfire Smoke page is a useful resource for more information about wildfire smoke and protection.