VCHRI experts Drs. Aline Talhouk and Lesa Dawson highlight the importance of early detection to improve long-term outcomes for the most lethal gynecologic cancer.

Each year, about 3,000 people in Canada are diagnosed with ovarian cancer. With symptoms that are vague and easily mistaken for less serious health issues, it can be difficult to detect in its early stages. As a result, many people receive their diagnosis when the disease is already advanced.

Despite these challenges, new research is driving progress in prevention, detection and treatment. Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute researchers Drs. Aline Talhouk and Lesa Dawson share what you need to know about ovarian cancer, including its warning signs and risk factors, and how innovative strategies are bringing science closer to earlier detection.

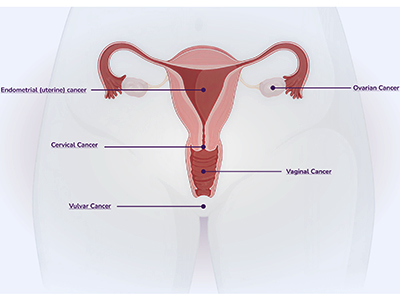

Q: What is ovarian cancer and how is it different from other gynecologic cancers?

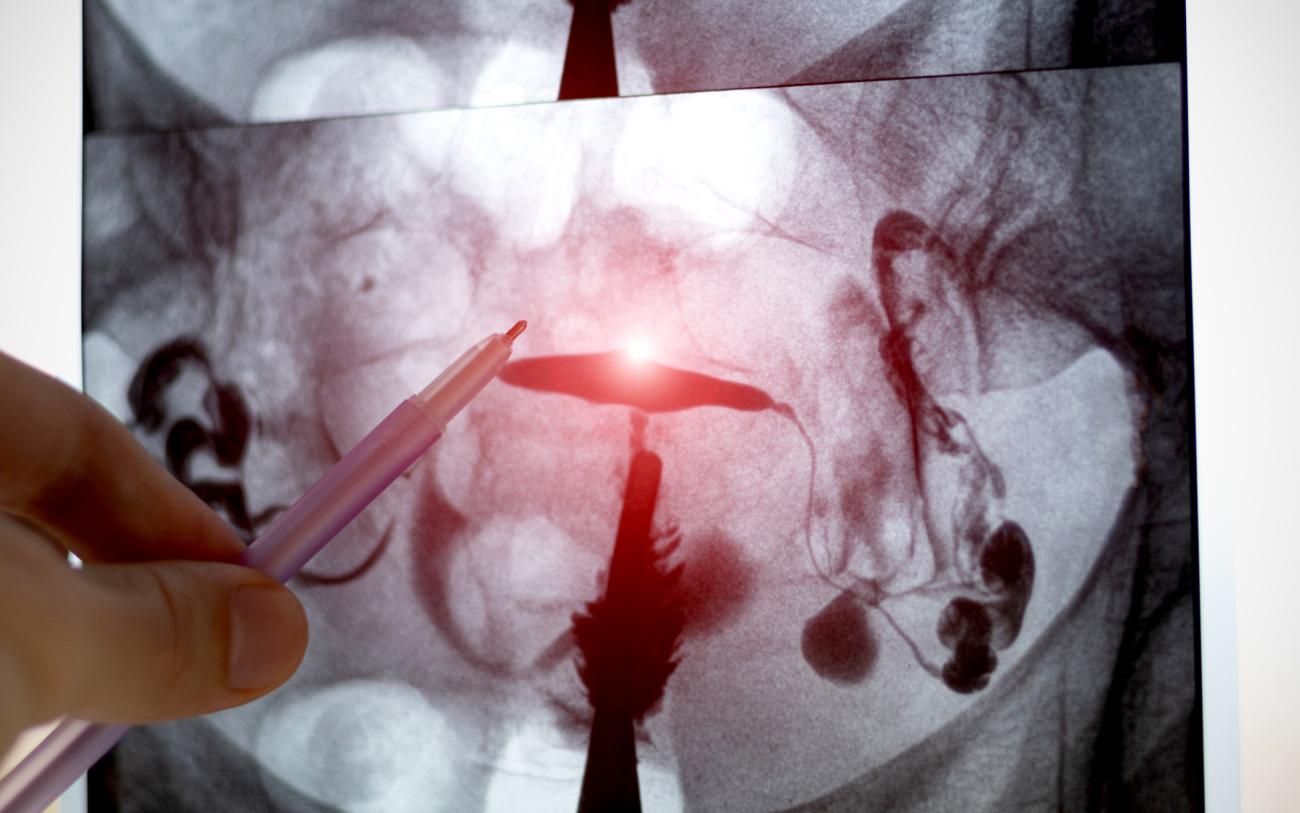

A: Ovarian cancer is a type of gynecologic cancer that affects organs within the female reproductive system. This includes the ovaries, which produce eggs and hormones, and the fallopian tubes, which allow eggs to travel from the ovaries to uterus. Some ovarian cancer cell types begin directly in the ovaries, but the most common type — called high-grade serous cancer — actually starts in the fallopian tubes.

Ovarian/fallopian tube cancer is unique in that it has no vaccine, no simple screening test and no single symptom of early disease. It causes more deaths than all other gynecologic cancers combined, mainly because these tumours often spread within the abdomen before they are discovered.

Q: What symptoms of ovarian cancer should I watch for and when should I talk to my doctor?

A: Spotting ovarian cancer early is challenging, which is why being vigilant about possible symptoms and understanding personal risk factors is important. Classic symptoms to watch for include:

- Persistent bloating or abdominal swelling that doesn’t resolve.

- Pelvic discomfort or cramping unrelated to the menstrual cycle that doesn’t resolve.

- Feeling full quickly after small meals or loss of appetite.

- Changes in urinary or bowel habits, such as more frequent and urgent urination or constipation.

- Changes in menstrual cycles or general fatigue.

- Lower back pain or pain during intercourse.

It is important to note that these symptoms can be caused by many benign conditions. However, if the symptoms are new for you, occur almost daily and persist for more than two weeks, contact your doctor.

Q: Can genetic testing help predict ovarian cancer risk?

A: Genetic testing can show you whether you carry certain inherited changes in your DNA that make you more likely to get ovarian cancer. The most common are BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations (BReast CAncer genes 1 and 2). Everyone has BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes, which normally help repair DNA, but some people carry inherited mutations which can lead to higher cancer risk. Other gene changes, like those linked to Lynch syndrome, can also raise your risk.

If you have a family history of ovarian, breast or certain other cancers — such as multiple close relatives with breast cancer, particularly if they are diagnosed under the age of 50 — or if you have Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry, you may be eligible for free genetic testing. Our research team is studying the idea of offering population-based testing, with the hope that everyone can be tested for BRCA mutations as part of routine care.

Q: What preventive options are available for people at higher risk?

A: Although there is no proven screening test that detects ovarian/fallopian tube cancer at an early stage, if genetic testing shows you are at higher risk, there are a few steps you can take to lower your chances of getting ovarian cancer.

People with an inherited BRCA mutation can preventatively lower their risk by surgically removing the ovaries and fallopian tubes, which is recommended for people who have completed having children. While this method significantly lowers the chance of getting cancer, a consequence of removing the ovaries is surgical menopause. To avoid this side effect, a new two-stage approach is being investigated where the fallopian tubes are removed first, followed by removal of the ovaries a few years later. The gynecologic oncology team at Vancouver Coastal Health is participating in two large, international clinical trials to further validate this approach.

Taking the birth control pill is another way that people with an inherited BRCA mutation can reduce their risk. Using the pill for five years or more has been shown to cut ovarian cancer risk in half in high-risk women.