Preliminary findings indicate that key sex differences in diabetic retinopathy disease presentation could be essential for precision diagnostics.

Sex differences could play a key role in diagnosing diabetic retinopathy, according to the results of a groundbreaking study led by Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute researcher Dr. Ipek Oruc. A condition that puts patients at risk of blindness, diabetic retinopathy may be more likely to progress along a given pathway depending on whether a patient was born male or female.

“The lack of sex- and gender-specific medical guidelines for diabetic retinopathy highlights the need for more research into the underlying mechanisms of these differences.”

Diabetic retinopathy is the most common cause of blindness associated with diabetes, affecting around one million Canadians. The condition is characterized by changes to tiny blood vessels at the back of the eye.

In the early stages, symptoms of the disease may go unnoticed, such as with mild to moderate non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy. However, once the condition advances, various vision-threatening complications may arise. Leakage from damaged blood vessels can lead to eye swelling — called macular edema — which causes vision loss primarily affecting central vision.

“If left untreated, around half of high-risk non-proliferative patients will experience progression to proliferative diabetic retinopathy within a year — making it particularly crucial to identify and manage the disease early.”

“Regular monitoring is crucial for detecting early signs of diabetic retinopathy and to prevent its progression to moderate or severe disease,” says Oruc. “However, aside from considerations during pregnancy — when females are at higher risk for progression — sex is not presently factored into disease diagnosis, management or treatment.”

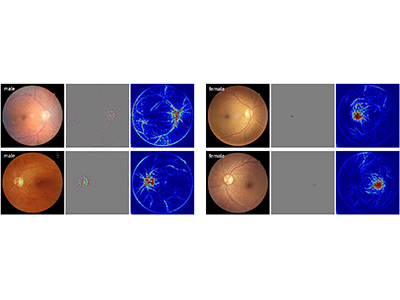

Researchers trained, validated and tested an artificial intelligence (AI) algorithm on a data set of 2,967 fundus images from 1,491 female and 1,476 male patients with diabetic retinopathy. The fundus is the inner area at the back of the eye comprising the retina, optic disc, fovea, macula and blood vessels.

The algorithm was trained to classify patient sex from retinal images of people with diabetic retinopathy. Male and female groups were matched for age, ethnicity, severity of diabetic retinopathy and hemoglobin A1c levels — a measure of blood sugar in the body — to prevent the model from using these potentially confounding variables when classifying a patient’s sex.

Oruc and her team used convolutional neural networks (CNNs) — AI algorithms specializing in image classification — to identify patterns of diabetic retinopathy presentation in the images. This approach builds on the team’s prior research on the classification of retinas by sex.

“CNNs can find patterns in images not readily apparent to the human eye, even among experts in the field.”

One of the research team’s central objectives was to find an empirical method to identify potential differences in how diabetic retinopathy manifests in females and males.

Sex-specific diagnostics could enhance diabetic retinopathy management

To see whether there were sex-specific disease characteristics of diabetic retinopathy, Oruc and her team used Guided Grad-CAM saliency maps — an explainable-AI technique that can peer into the often mysterious ‘black box’ of CNNs. While CNNs can identify unique features in a series of images, the explanatory AI built into Guided Grad-CAM saliency maps helps researchers understand how the CNN arrived at its conclusions.

“For example, if we were to use explainable AI to identify what distinguishes a celebrity from other people, it may highlight the celebrity’s nose and mouth as important features that set that celebrity apart,” Oruc says.

The Guided Grad-CAM saliency maps showed that the CNN focused on the macula in female fundus images and the optic disc and peripheral branching vasculature from the optic nerve in male fundus images.

“This pattern differed noticeably from the saliency maps generated by CNNs trained on healthy eyes, which did not highlight these particular regions, indicating that diabetic retinopathy may manifest differently by sex,” says Oruc.

“However, further research is needed to validate this hypothesis,” she adds, which is why her team is presently conducting a follow-up study.

“If confirmed, sex-specific disease indicators could have significant implications for the diagnosis, management and treatment of diabetic retinopathy.”

The research team’s application of CNNs — interpreted using Guided Grad-CAM — was able to achieve a high level of accuracy using a smaller dataset for training the algorithm than is typical, Oruc notes. “This is particularly important, as large datasets are more costly and time-consuming.”

“The success of this approach with a small dataset puts studies like ours within reach of other research teams with limited resources.”