Researchers are learning how what we eat affects the gut and influences conditions like kidney stone formation.

Kidney stone disease has been on the rise in Canada over the past 25 years and researchers believe that the gut microbiome is at least partly to blame. The condition affects between six to 12 per cent of Canadian adults, with around 50 per cent of these individuals experiencing recurrent kidney stones.

“We know from interviews with patients with kidney stone disease that preventing recurrent stones is their primary goal for improved quality of life,” shares Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute researcher Dr. Dirk Lange. “As such, it is important for research to focus on understanding the origins of kidney stone disease and its various risk factors.”

In a manuscript published in Urologic Clinics of North America, Lange and his team reviewed research on the connection between kidney stone disease, microbes and processes in the gut microbiomes of individuals with recurrent kidney stones.

If you were to take a tour through your gut, you would find trillions of microorganisms, mainly bacteria. Many of these bacteria work together to break down food and extract nutrients, with the nutrients and metabolites produced in these processes key to maintaining overall health. However, imbalances in the gut microbial community can lead to dysbiosis: a reduction in good bacteria and overgrowth of harmful bacteria that can make individuals affected more susceptible to disease.

Oxalobacter formigenes helps break down oxalate — one of the main components in stones — in the gut to prevent stones from forming. However, supplementing with an Oxalobacter formigenes probiotic did not reduce the uptake of oxalate by the body and did not reduce the risk for stones to form. Likewise, other studies found no difference in Oxalobacter formigenes abundance between people with calcium oxalate kidney stones and healthy controls.

“Kidney stone disease is characterized by the formation of crystal deposits in the kidney and is often associated with intense pain, resulting in emergency room visits for the urgent management or removal of stones to prevent long-term kidney damage.”

More recent studies that used genetic sequencing to zoom into the gut microbiome found a lower presence of other oxalate-degrading bacteria, namely Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium, in individuals with kidney stone disease. This, Lange shares, points to a potential harmonious relationship between Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium and Oxalobacter formigenes.

“What we see in these studies is that oxalate degradation likely requires a network of bacteria that work together symbiotically to support one another in order to effectively process and degrade oxalate in the gut,” Lange explains. “Probiotic supplements that included these other oxalate-degrading bacteria were found to reduce oxalate levels in the body. However, more research is needed to determine how relevant this connection could be to preventing stone formation.”

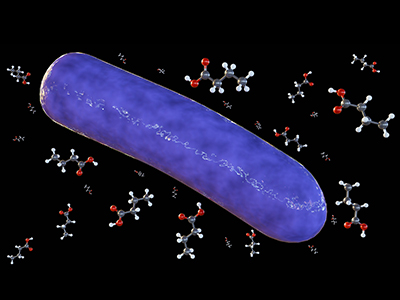

The link between fibre, healthy gut microbes, butyrate and kidney stones

Another key characteristic of gut microbiomes in people with kidney stone disease is that they have fewer butyrate-producing bacteria and less of butyryl-coA synthetase, which is needed for bacteria to make butyrate. Butyrate is the byproduct of healthy bacteria in the gut and the result of breaking down fibre in the large intestine, a.k.a., the colon.

Lange and his team noted that, while butyrate in kidney disease is still an emerging area of investigation, there are many indicators potentially linking it to oxalate removal in the gut and reduced inflammation in the kidneys.

“We now know that the microbiome of stone-producers has lower capacity to produce butyrate. So, increasing butyrate in the gut could reduce stone formation.”

“Something we are looking into now is whether a butyrate-producing supplement called tributyrin could be used to enhance butyrate levels and reduce stone formation in people with recurrent stones,” Lange adds.

Lange’s review also highlighted a possible connection between how the bodies of people with kidney stones process vitamins and their ability to balance minerals, inflammation and oxidative stress. In particular, people with kidney stone disease were found to be lacking in vitamins B2, B5, B6, B7 and B9. However, additional research is needed to fully explore the links between deficiencies in these vitamins and kidney stones.

“We know that people have a higher risk of developing kidney stones if they have a history of taking oral antibiotics, particularly in early life,” notes Lange. “Antibiotic exposure is disruptive to the microbiome, and can lead to microbiome imbalances.”

“What remains is to further our understanding of how the stone-associated microbiome imbalance changes the overall function of the microbiome, driving the formation of kidney stones. That is the first step toward developing novel preventative and curative treatments.”