Researchers map uncharted territory in the dying process, with potential implications for end-of-life, emergency care and organ donation.

Despite being a natural part of the lifecycle, much is still unknown about the process of dying. In their groundbreaking study, Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute (VCHRI) researcher Dr. Mypinder Sekhon and PhD candidate Jordan Bird reframe the moments before death as a biological transition, rather than a single moment, filling in missing pieces of the puzzle to understanding the final stages of life.

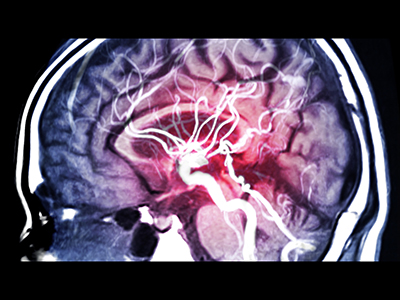

“Historically, it was assumed that, during the dying process, a decrease in blood flow to the brain and the rest of the body occurred simultaneously, with similar effects in terms of decreased functionality,” Sekhon contextualizes. “However, our study identified that a more complex and phased process is taking place.”

“Our findings provide preliminary evidence that cessation of brain blood flow may occur earlier in the dying process than is stated in current clinical assessments and guidelines.”

Using equipment funded by VGH & UBC Hospital Foundation donors, researchers found that a cessation of blood flow to the brain and a decrease in the ability of its tissues to uptake oxygen occurred before electrical and mechanical activity in the heart stopped. They also found that brain oxygenation ceased before blood flow throughout the circulatory system.

"These findings have pertinence for multiple fields, including critical care, resuscitation, organ donation and palliative care.”

“In lifesaving care settings, such as with patients admitted to emergency departments during critical illness, it may be appropriate to initiate cardiopulmonary resuscitation and augment or stabilize blood flow even sooner than we previously thought to preserve brain functionality,” says Sekhon. “This could mean starting these interventions based on an assessment focused on the brain, as opposed to solely relying on a heart or peripheral pulse assessment.”

More reassurance for patients and families during planned dying

Sekhon and Bird’s study is the first to use a multimodal approach to monitor brain blood flow and oxygenation during the dying process. Their research involved brain and body blood flow and oxygenation monitoring among 39 patients who underwent the withdrawal of life-sustaining measures, along with 12 healthy controls.

On top of having implications for critical care, Sekhon and Bird’s study identified several important considerations relevant to resuscitation sciences, planned dying and organ donation. Importantly, their research validated that a multimodal approach to studying the dying process in humans is possible.

“We also discovered that brain blood flow and brain tissue oxygenation ceased before cardiovascular function in all patients, albeit with slight variations between patients and brain locations,” says Sekhon.

Additionally, they found that having a preexisting heart condition, which weakens the heart muscle, likely leads to a steeper decline in blood pressure, speeding up the dying process.

“This information not only deepens our understanding of the dying process, it can also help us to better predict how long the process will last in patients,” says Bird. “Knowing this can offer peace of mind to patients undergoing planned dying and their loved ones, providing them with more information about what the dying process might look like.”

Sekhon and Bird’s research can also inform evolving definitions of dying. The 2023 Canadian Brain-Based Definition of Death Clinical Practice Guideline defines death as the permanent cessation of brain function, brain-based consciousness and brain stem reflexes, which also includes the inability to breathe independently.

The research team’s findings also pave the way for a potential re-examination of organ donor practices and resuscitation sciences, and could offer unique insights into the brain’s vulnerability during the dying process.

“An impetus for this study was a case in which a young individual undergoing palliative care was unable to donate his organs after not meeting a threshold for death in time to preserve his organs for donation,” Bird shares.

“The young man’s family was dismayed by the inability to follow through with his wishes,” adds Bird. “It is something that our research and further studies could help to address.”

Sekhon and Bird are continuing to pursue research into the dying process, looking at the effects of dying on different regions of the brain and, in particular, among patients who wish to be organ donors.